7 common misconceptions about patents (and what’s actually true)

In my work as a patent attorney, I regularly encounter persistent misconceptions about patent protection. These misunderstandings can quietly lead to poor strategic decisions or missed opportunities. In this blog, I outline the seven most common misconceptions and explain how things really work.

1. A patent means I’m free to bring my product to market

What’s counterintuitive about a patent is that it is essentially a negative right. It gives you the right to prevent others from making, using, or selling your protected invention. It does not automatically give you the freedom to commercialise your own product.

Your product may include elements that are covered by existing patents held by third parties—and in practice, that is often the case. Most innovations build on or rely on existing technology. That’s why, before launching a product, it is wise to conduct a Freedom to Operate (FTO) analysis. This assesses whether commercialising your product would infringe the patent rights of others.

2. I need a fully working prototype first

A working prototype is not a requirement for filing a patent application. What matters is that your invention is technically substantiated and described in sufficient detail for a skilled person to understand and reproduce it.

Building a fully functional prototype can take considerable time. In some cases, that delay increases the risk that a competitor files a patent for a similar invention before you do.

Moreover, a patent application rarely focuses on just one specific embodiment, even if that is your preferred version. Together with your patent attorney, you explore all possible variants and implementations of the invention, allowing the scope of protection to be drafted as broadly and strategically as possible.

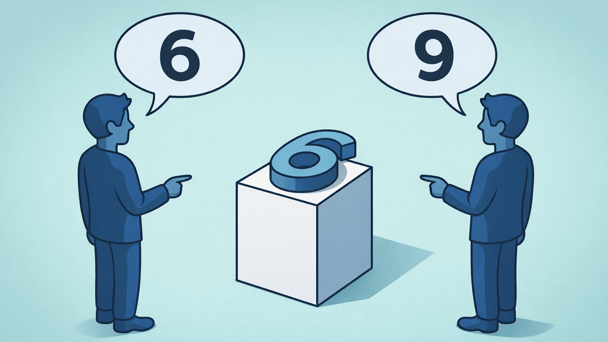

3. Patents are only for highly complex inventions

To be patentable, an invention must be new and inventive. In practice, the bar for inventiveness is often lower than many companies expect.

Inventors, especially those deeply familiar with their technology, frequently assume their solution is too obvious to qualify. But when you look closely at the development process, innovation usually consists of many intermediate steps. Taken together, those steps can amount to a genuine inventive leap.

Think of the paperclip or the Post-it note. Neither is technically complex, yet both were patented.

4. Only physical products can be patented

Patents are not limited to tangible products. Processes, software-related inventions, and new applications of existing technology can also be protected.

Examples include more efficient or environmentally friendly manufacturing methods, or a new use for a known material. In the pharmaceutical sector, patents are regularly granted for new medical uses of existing drugs—for instance, when a known compound proves effective for a different condition under a new dosage regime.

5. Patents are only for large companies with deep pockets

Patent protection is not reserved for multinationals. Start-ups, SMEs, and even individual inventors can apply for patents.

By choosing the right filing routes, costs can be spread over time, making patent protection more accessible. For start-ups in particular, patents have clear strategic value: they demonstrate exclusivity and reduce investor risk. In funding rounds, that can make a decisive difference.

6. The best patent offers worldwide protection

In practice, truly global patent protection does not exist. Even large corporations limit their protection to a strategic selection of countries often eight to ten at most.

The choice of countries depends on several factors:

- Where are your key markets?

- Where are major competitors located?

- Where are potentially infringing products manufactured or distributed?

Common choices include the United States, China, Germany, and France. This targeted approach offers effective protection at a manageable cost, without paying for coverage in countries where it adds little value.

7. There is an authority that enforces my patent for me

Patents are not automatically enforced by a government body. As the patent holder, you are responsible for monitoring your rights and deciding how to act if infringement occurs. There is no enforcement authority that does this on your behalf.

If you suspect infringement, you decide whether and how to respond. Legal action is one option, but not the only one. In many cases, a formal cease-and-desist letter pointing out your IP rights is enough to stop the infringement. It does not always have to escalate into litigation.

Overigens is in veel gevallen een aangetekende brief aan de inbreukmaker waarin je wijst op jouw intellectuele eigendomsrechten voldoende om de inbreuk te stoppen. Het hoeft echt niet altijd tot een juridisch geschil te komen.

Read our series on patent infringement for practical guidance on enforcement and on how to avoid infringing the rights of others.

Questions about patent protection?

Do you have questions about your specific situation, or would you like to know whether your invention is patentable? Feel free to contact me for an informal conversation. I’m happy to think along with you about the most effective strategy for protecting your innovation.

About the author

My journey into intellectual property started during my graduation project on nanotechnology at IMEC, where I first encountered the world of patents. The seamless intersection of technology and law...

More about Jeroen >